CONTEXT: A prior online posting from my 2016 tour in Europe, which began in Paris (where I’d been 4 times before). This is the only one of my INTRODUCTORY MATERIAL pieces for this blog that I have extensively expanded from its brief original, done to re-affirm here my affection for, and joy in, French culture and aesthetics. Many of my postings from Germany (some of which will appear in the TRAVELS category/tag here) are much longer than my captions of photos taken in my first destinations, Paris, Venice and Salzburg were. This is because German power, ambition and excess so impacted the 20th Century that once I had originally started posting those online with explanatory captions, I often felt moved to compose long, quasi-essays for pictures I took in Berlin and after, discussing their implications within an historical setting.

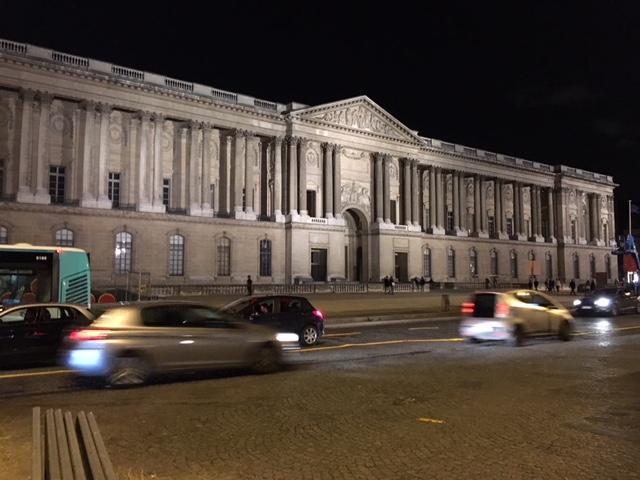

But this view is one of my very favorite marvels of anyplace I have traveled, a breathtaking apparition of sheer majesty – a reason for admiration, not meditation. So I have enlarged my original caption for it in honor of how dear it is to me personally. And in hopes that any visitor to Paris may come to seek and savor this vision of loveliness; overlooked, like Cinderella – but unlike her, with a well-scrubbed surface.

To my eyes, this may be the grandest façade anywhere, a perfect combination of ideal proportion and regal demeanor. Despite its auspicious location at the eastern end of the world’s greatest art museum, it is overlooked by many visitors to Paris, overshadowed by the main entrance to the galleries dominated by I.M. Pei’s glass Pyramid portals. At one time, this was the main entrance to the palace, and if now often underappreciated, its cool, elegantly understated aesthetic (the work of a committee, though mainly credited to Claude Perrault) is keenly admired by perceptive architects and art students.

And by me. Paris’ sumptuous pre-World War I, ‘Belle Epoque’ architecture is the city’s most immediate, attention-grabbing appeal for me, and this exterior (some 200 years older than the period cited above) is in my opinion the very best of the best of that rarefied standard: The pinnacle compliment I can pay. Imitation is the sincerest flattery, and this has been a basic template for palaces and other uniquely illustrious buildings elsewhere, ever since its completion. It is visible evidence, imperturbable in granite, of how far above the ever-present squalor of life our ingenuity can enable us to rise.

Ironically, though this front was meant to be a suitably noble prospect for a principal royal residence, it had that status for only a short time. Within a few years of its being finished in 1670, France’s King Louis XIV, who had commanded it to be built, left it and Paris behind. A main reason for this was that he distrusted the city because of political violence that had threatened him there when he was a child monarch. And no doubt the scope and impression of this addition to the Louvre was partly intended to awe the local populace as a display of absolute royal power.

Nevertheless, by the mid-1670’s Louis was creating his huge new palace complex at Versailles, then about an hour’s swift horseback ride from central Paris. Not only did his permanent relocation to Versailles by 1680 allow Louis to avoid the potential tumult of his capital (along with its noise, smells, pestilence etc.), but that vast residence was purpose-built to house a full royal court where all the important aristocrats of France could be gathered, housed, diverted – and discreetly kept under the watchful eye of the regime, far from their own domains, where they might misuse their unchecked local authority.

Personally, I find the Descartes-like austere grandeur of this design more handsome than the sensuous Baroque exuberance of Versailles. I don’t know if Louis regretted having to leave behind a setting magnificent enough for one who styled himself ‘le Roi du Soleil’ (the Sun King), but this marvelous construction – still virtually brand new then – more or less languished after his departure, with little regular role in royal life. And such was the unregulated density of Paris at the time that common hovels got built nearly up to these very walls (as at Notre Dame), till all of those were removed as the city was rebuilt for orderly urban function in the mid-19th century, partly to give less cluttered surroundings and more edifying views of such venerable edifices.

I strongly recommend that you seek out this spectacle of reserved stateliness if you visit Paris. Like many of her great sights, it is floodlit at night; this picture was taken on a Saturday evening when thousands of Parisians strolled this neighborhood of illuminated, world-famous landmarks. As noted, locals seem to take their epic cityscape for granted – what a fantastic privilege! – but they evidently occasionally disregard the familiarity of their extraordinary surroundings, to acknowledge and fully appreciate them.