Mightier than the Sword?

‘Omnia Gallia,’ Latin for ‘All of Gaul,’ is a term Julius Caesar used when writing about ‘Gallia,’ now the territory of France. My surname is Gaul (Irish, not French), and I wanted the flexibility to write about whatever attracts my interest; that is, any aspect of my experience, or of intriguing matters beyond it. As an amateur historian, cultural observer, and Gallophile (a lover of things French), I will try to capture and sharpen my thoughts on matters that allure me, then share them here.

So ‘Omnia Gallia/All of Gaul’ seemed like a rather suitable blog name.

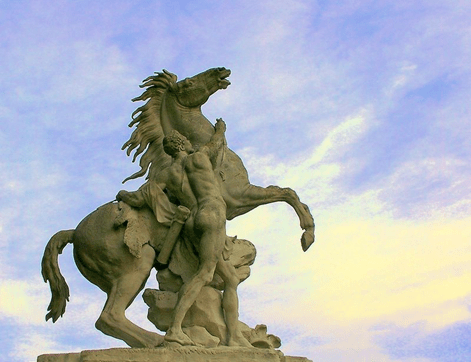

And to represent my approach to this project, above is an image of one of the Horses of Marly (Chevaux de Marly), imposing statues that mark the start of Paris’ Champs Elysees. Aside from being superb icons of French culture, these statues symbolize for me how wondrous the enterprise of life can be. Sometimes a struggle; often a hard, but rewarding undertaking. Illustrated here by a mighty horse harnessed and conducted with beauty, grace and genius, by human vigor, sensibility and reason – which may appear in any, and all of us.

That’s imagery enough to suggest my goal here: To ride wherever, whatever, inspiration transports me.

From the Horses’ sculptor Coustou, to the masons who wrought their stately pedestals, the draymen who moved them to the site undamaged, the pavers who precisely fitted the stones of the grand avenue they would enhance, etc. Every one of those deeds is part of a continuum of ‘human genius,’ of which no other beings on this Earth are capable. Even if talents are not equivalent contributions (and in any case, are bestowed by random genetics) they are all essential, and vary in their importance depending on the circumstances (e.g., the lowly pavers’ expertise made Paris’ grand boulevards like this one, worthy of marking with the Chevaux).

I am just a retiree living in modest comfort in Chicago; nobody influential. However, the ‘Mightier than the Sword?’ subtitle reflects my wish that my keyboard/pen might be resonant, persuasive, but not demanding – i.e., coercive or sword-like – about the point of view, if any, I wish to propose or advance. Or at least to try to offer readers something worth reading and considering.

I am no academic, so writing here, will explicitly try to connect to laymen like myself. I intend and hope that any reasonably well-informed person can – with moderate effort – understand my posts. Even if he or she thoroughly disagrees with their point, if any.

Generally speaking, I see it as useful to advocate for hope in many cases when despair would be easier. Advocating for validation by our collective experience, not just our individual achievements, I try to articulate things that many people likely privately think, feel or simply need to believe. Such as the premise that Life is worthwhile and benign, despite all evidence that it is not. To give substance to perceptions held by people who rarely speak of them aloud, and may even feel conflicted to admit to themselves. Even if they might benefit from them personally, and even consequently help make a better World.

For example, of the necessity to make full use of our Reason, but its insufficiency as a substitute for Heart – that is, for empathy – in reaching the fullest expression of our ‘Humanity.’ Whether individually, jointly or collectively.

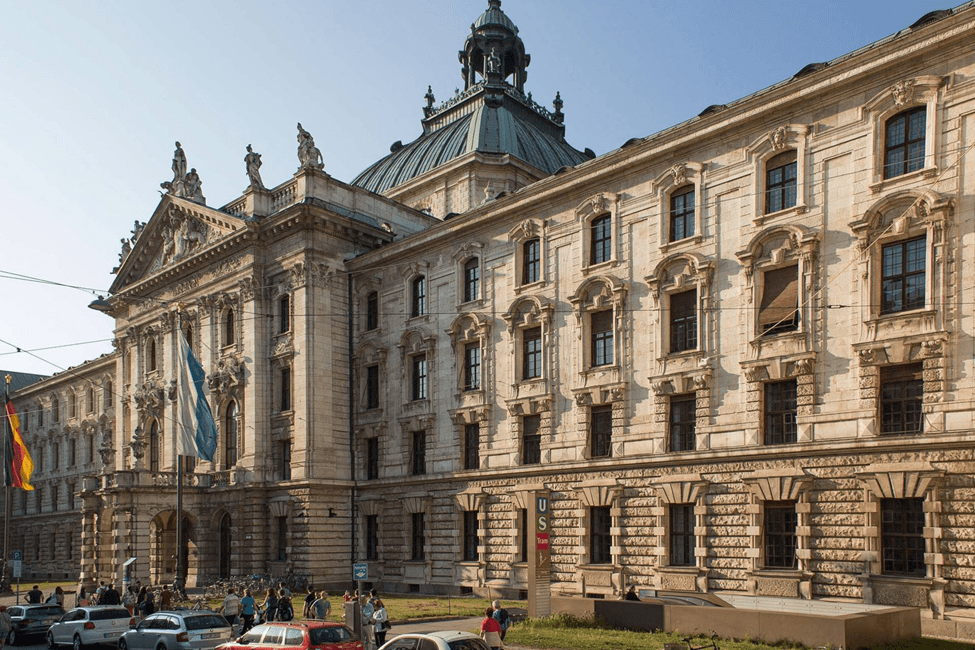

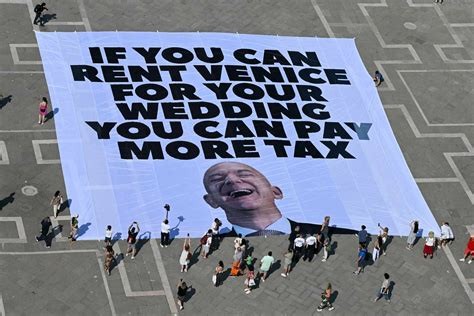

To initiate OmniaGallia, I will re-post items that I wrote and posted online before, most of them photos and captions from my trip to Europe (just before the U.S. Presidential election of 2016) to acquaint readers with my style. My first posts here will be tagged ‘Introductory Material,’ selected as examples of my priorities and sensibilities. Other re-posts from my 2016 tour (which started in Paris, went to Venice, Austria, Germany, and ended in Amsterdam) will be categorized as ‘Travels.’

I will also add material here I have written as personal meditations, categorized as ‘Journey.’ Anything I post/re-post here that doesn’t fit either of those headings will be ‘Caprices.’ And of course, I will gradually be adding new material here, composed explicitly for OmniaGallia.

Intrigued? Puzzled? So am I, most of the time. Come along, and let’s see where all this may lead.

Bryan Gaul