CONTEXT: After the forbidding Brutalist image of the anti-aircraft Flak tower, here is a contrasting sequel to both its appearance and purpose, less than half a mile away. In my post about the Ann Frank House’s relative nearness to the museum with Rembrandt’s revelatory ‘The Night Watch’ (posted July 17, 2022), I remarked the irony of that proximity: ‘a summit and an abyss of human endeavor, separated by a brief walk, yet from different worlds.’ And that contrast is reflected here also – with no poignant side-story like Anne’s – though this post contains a story of a different sort of tragic loss.

Few people alive today remember military conflict on a global scale like the second World War, but spectacles like that Flak Tower (and awareness of all the resources wasted on such things) may help drive home the message that national combat is the most pervasively awful, perversely counter-productive sorrow we inflict on ourselves. A British observer of World War I wrote of its devouring trenches, machine gun nests, high explosives, poison gas, etc., ‘It is all the work of the Devil.’

And so it is; in whatever guise ‘the Devil’ may take, trying to supplant our finest efforts and aspirations – such as are amassed on Berlin’s Museum Island – with our very worst ones. Unless one considers absolute indifference to the well-being of others a virtue, there is nothing noble, let alone, glorious about War – something about which we, who lack personal experience of it, must never let ourselves be deceived.

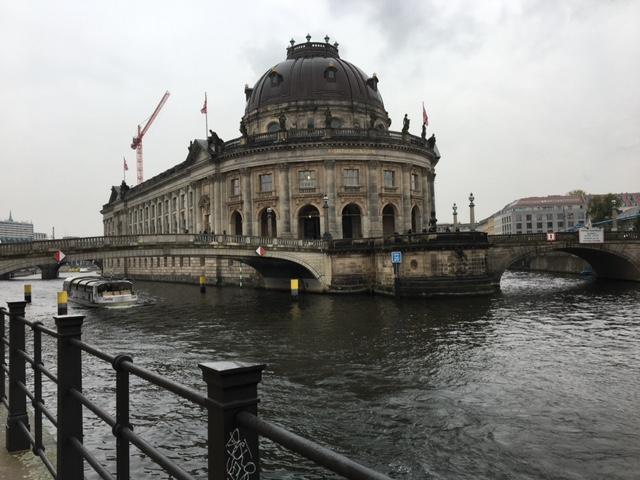

In another of my 2016 posts, this building appeared above a colorfully lit tour boat on the Spree river at night, a display of Berlin’s festive impulses. Germany’s capital is said to exploit its warm months more than any other city in Northern Europe, with an overabundance of outdoor events and pursuits. This was not so visible when we were there in mid-October, but the city felt very lively in any case. Even though signs of its destruction due to its role as Hitler’s capital can still be noticed, and it still suffers in the world’s consciousness from its (none too willing) association with him, it is not just a haunt of evil memories.

This building sits at the prow of Berlin’s Museum Island, home of a remarkable assembly of exhibition spaces for art owned by Prussia’s kings, and after 1871, by the Kaisers of the German Empire. Aside from this one, the Island is home to the Neues (New) Museum, the Altes (Old) Museum, and the Pergamonmuseum. The latter houses full-scale recreations of architectural elements from Middle Eastern antiquity, including the Ishtar Gate from Babylon. The seminal bust of Nefertiti, an ancient queen of Egypt, is in the Neues Museum.

The Bode Museum now displays sculpture. Originally it held Germany’s national painting Gallery, but after Communism fell and the city was re-united after 1989, the decision was made to move that collection to the new Gemaldegalerie in the Kulturforum (a district of cultural institutions – including the still-unconventional Orchestra Hall, the Philharmonie – south of the Tiergarten Park, created to replace arts venues destroyed in the war).

Or I should say, what remained of the national painting collection got moved. A void in today’s gathering of Old Master paintings (mostly German, Dutch, Flemish and Italian Renaissance) at the modern Gemaldegalerie is a wrenching reminder that violent struggle causes irreplaceable loss beyond human lives. Shortly before World War II, when it became apparent that aerial bombing was likely to be a part of any new military conflict (largely the fault of the Germans themselves, having prepared to greatly expand and enhance air warfare), major cities in the prospective combatant nations made plans to get their movable local treasures out of harm’s way.

Berlin did the same, evacuating much of the great art housed there to safer locations around the country. But there were many paintings in the Bode Museum (then still called by its original name, the Kaiser Friedrich Museum) too large or fragile to be moved. So when it was struck by Allied bombs dropped with the crude targeting mechanisms then available, a number of such monumental pieces were destroyed and lost forever; not just to Hitler’s Master Race, but to all of us. Presumably other treasuries on the Museum Island were also damaged in the bombing – as was the sumptuous Protestant Cathedral there – but I don’t know if their collections had already been removed.

(Something similar happened in the firebombing of Dresden; much of the music of Schuetz, a marvelous late Renaissance German composer which had never been copied, was incinerated and simply gone, depriving us all of whatever joy and delight it might have afforded.)

Today, the Gemaldegalerie, while rich in the modest-sized paintings that could be removed and thus preserved, is notably lacking in larger works. Their absence is a visual echo of how barbarism can tear at the fragile fabric of civilization. Part of Art’s purpose and mission is to moderate human behavior, but it cannot withstand fully unleashed passion; a burst of animal savagery can cause the work of the Ages to be undone.

And at this museum, in Hitler’s Berlin, it did.