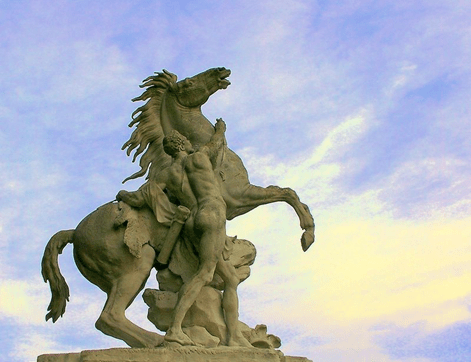

CONTEXT: As a self-styled historian, for me, going to Berlin was the linchpin of my 2016 visit to Europe, due to the city’s (not entirely willing) role in Nazism. Fellow traveler Paul and I visited Charlottenburg Palace, seat of Prussian kings, just west of central Berlin. The palace had no connection to the Nazis, but I used this statue – similar in spirit to ones I’d seen elsewhere in Austria, another German-speaking land, and at a Hapsburg castle in Prague – to propose a rarely-noted factor in why a flower of evil like Hitler might have sprung – germinated? – in German soil.

This statue of King Fredrick William I of Prussia, in Charlottenburg Palace’s courtyard was, of all the monuments I saw in Austria or Germany, the one that seemed to most bluntly portray strength as the greatest (or only) virtue. The captives below the king’s horse writhe in terror at his sway, but he does not even bother to look at such wretches; instead, he gazes off to infinity in search of something more worthy of his noble eyes.

When this statue was made, kings were seen as bulwarks against the inherent chaos of life. However, the fact that Germans, in particular, seemed to not only accept such arrogance and menace from their rulers, but to approve and admire them, may obliquely help explain the attraction of Hitler.

This attitude may be rooted in the fact that the deepest national trauma of the German people before World War II was the Thirty Years War of 1618-1648, the worst of which was fought in their territory (there was no single “Germany” then, just dozens of small German-speaking states). That ghastly conflict was even more destructive than mechanized warfare; what troops then lacked in lethal technology, they made up in vigorous bloodlust.

In addition to soldiers’ deaths, about a third of the civilian population of “the Germanies” is thought to have perished, killed outright, or died of starvation, epidemics, and other miseries that flourished in the general pandemonium. Crops went unharvested or could not get to hungry markets via roads infested with bandits, commerce and crafts collapsed in the turmoil, etc. Civilization in these lands broke down then about as much as it possibly could.

Much of this horror happened at the behest of powerful neighbors, especially France (already a united realm), which wanted Germans to stay divided and feeble. From then on, the terrible cost of weakness was embedded in their folk memory, leading to an ingrained assumption that to be strong was to be “good.” The lesson the nation seems to have absorbed at indescribably dreadful cost in the 17th century was that without power, nothing else mattered. In fact, the King portrayed here was pivotal in giving Prussia a pervasive military disposition, partly in response to dire experience: helplessness had yielded horror.

In 1871, German lands that had so often been at the mercy of others, were finally united under a single Prussian-led regime, as the German Empire: The Second Reich (the First Reich was the Holy Roman Empire). But when the still relatively new unified ‘Germany’ was defeated in the Great War (World War I), many Germans wouldn’t accept that their talented, progressive nation, a major driver of the Age of Reason and Industrial Revolution, a dream unfulfilled for centuries, was not invincible.

Such people were susceptible to sinister explanations – especially to ones hissing that if their mighty Fatherland had been defeated in battle, it could only be due to some treachery. This suspicion was the mud onto which Hitler would cast seeds alleging a Jewish conspiracy – called ‘a stab in the back’ – to keep Germany from attaining some glorious destiny. (In this implausible telling, the pivotal intervention of the U.S. in the war in 1917 did not affect its outcome; only betrayal led to defeat.)

Added to that resentment was the factor that democracy, post 1918, was still relatively new to this society. The Kaiser’s abdication had led to the country becoming a republic, but many Germans reacted that perhaps they were culturally better suited for their prior authoritarian rule than parliamentary self-government. Especially when democratic politics did not solve their grievous economic woes during the Great Depression. And if they couldn’t have another Kaiser, they would have a Fuhrer – Leader – to dominate them.

All this may seem like a lot to extrapolate from one statue. Of course there were other factors in the rise of Nazism: unjust provisions of the Versailles Treaty (which was negotiated by the spineless ‘Weimar’ republic) – valid grievances Hitler exploited ruthlessly. But this statue, and monuments in the same vein throughout Germanic lands, suggest an undercurrent of power worship, which may well be at least part of why Nazism appeared, then broadly appealed, there.

Any culture that would consider an image like this normal – even praiseworthy – probably needed less convincing than most that Might Makes Right.