CONTEXT: This was taken from my original online posts about my trip to Europe in October, 2016. Other posts from my visit to Berlin gave more context about this site, for example, that the Gestapo building had originally been the Prussian Academy of Arts; hence the reference here to ‘art school studios.’

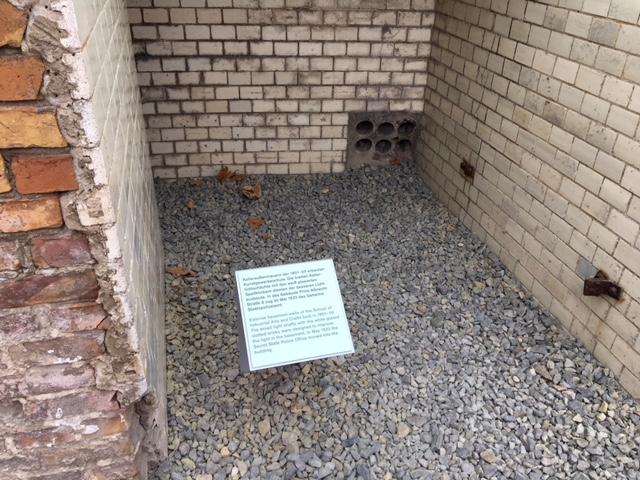

Detainees were held in these underground cells; with walls of common white industrial tile, this might be any basement in the world if one didn’t know what it had been. Gestapo staff routinely tortured prisoners during questioning on the destroyed building’s top floor, where the art school studios had been, but these tiles presumably witnessed immeasurable fear, pain and sorrow before and after such interrogations.

When a site of atrocity shows no evidence of it – just tidy, white walls – the mind’s eye conjures images. The ones I saw were horrific, so I couldn’t treat this as just some generic place of interest; its searing poignancy pleaded for a gesture of sympathy, however seemingly pointless, for what had been endured here. So I gently stroked the smooth surface of these tiles, as if to soothe agony one could imagine seeping through their coating and still being there, in need of comfort. None of the staff told me to stop; I almost certainly wasn’t the first to do such a thing.

Surely, in such a setting, no compassionate impulse, however clumsy, impractical or non-rational should be suppressed; and stroking those tiles was the only one I could think of at that moment. Deliberate suffering of the magnitude inflicted here degrades all of human experience, and thus transcends time; it felt urgent to be empathic to it, no matter how long ago it happened.

But if this place, foremost, saw cruelty and horror, it must also have seen Olympian courage and nobility. Presumably only high-value suspects would have been brought here, major spies, ranking prisoners of war, officials of resistance movements in occupied countries or Germany itself – people the Gestapo thought had precious knowledge that they would do anything, and everything, to extract.

We should remember and honor the bravery many of them must have shown, facing the most terrible circumstances, a price often worse than death paid to save the world from Nazism. Heroes died under hideous torture in this building, rather than yield information that could have cost thousands of Allied lives, or even altered the course of the war. The secrets they defended – despite having their teeth and fingernails torn out, and even worse – surely helped destroy Hitler.

One may find cause to have hope for humanity, even in the most awful, unlikely settings – indeed, perhaps especially in them. Here, men and women, aware they were being tormented for the sake of something far greater than their own lives, found the strength to withhold things the Gestapo was furious to learn, things on which the very fate of our species – its progress, or its eventual regression – might have pivoted.

The evil done in the structure that once stood here was incalculable – but not insurmountable. Within it, some of the darkest depths and brightest heights, the very worst and very best, of human nature contended and played out. And surely, the better side sometimes won, mightier than all the savagery deployed against it.

Thus, blood shed here helped water a rose of freedom.

For me, that is enough to sustain faith that all mankind is not corrupt beyond redemption. That faith is my tribute to all those who suffered here for posterity’s sake; it would feel ungrateful to yield to cynicism, as if their glorious example and sacrifice were for nothing. Valor that inspiring is never “for nothing,” but the heroism sometimes shown here helped rescue the honor of our race from the primal stain that Hitlerism was.