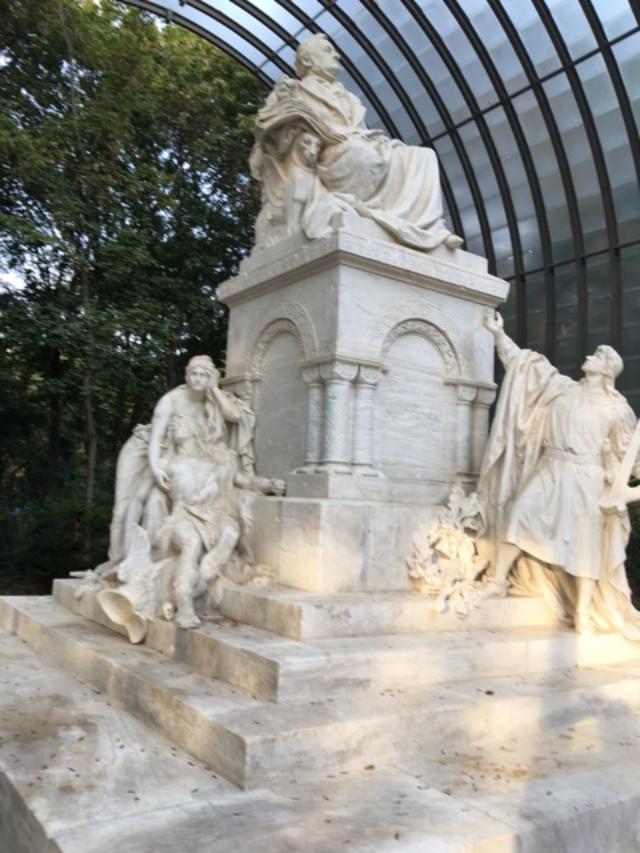

On the southern edge of Berlin’s main public park, the Tiergarten, stood this elaborate monument to Richard Wagner, arguably Germany’s greatest operatic composer, creator of “The Ring of the Niebelung,” etc. It shows Wagner seated on top gazing at some unseen Valhalla, with other figures, presumably characters from his works, beneath him. I don’t know why the protective overhead canopy was added; maybe his memory is considered too precious to be exposed to the indignities of Nature?

In most places, a memorial to Wagner would just be an edifying tribute to creative genius, but in Germany, events have given his memory darker overtones. His career began in the mid-19th century, well before German unification, but as a strident nationalist, he was considered one of the new German Empire’s artistic godfathers (as Verdi was, for Italy). He set to music ancient Teutonic myths which not only praised heroic values, but offered shared national legends to Germanic peoples – Prussians, Bavarians, Saxons, Hessians, etc. – united by language, culture and experience, but long politically separated.

Before and after the founding of the Empire, Wagner wrote music that portrayed Germans as a noble, chivalrous, valiant – and martial – race, and which continued to define and nourish the new country’s sense of identity. Having finally achieved their long-thwarted dream of single nationhood, many Germans reveled in how Wagner depicted their origins and glorified their virtues, seemingly now also manifest in their thriving land’s great feats of science, industry and the arts.

Wagner died in 1883 (well before Hitler was born), but after Germany’s defeat in the Great War/World War I, resentful nationalists continued to be agitated by his works. Hitler, a rabid believer in inherent ethnic superiority, was a fanatical Wagnerian – as much for his message as for his music. Also, Wagner had been well-known as a cultural (if not violent) anti-Semite, considering Jews an alien adulteration of pure German blood and culture – though there is evidently debate as to whether, or how much, Wagner might have approved of the Nazis and their goals.

(I’m not qualified to have a scholarly opinion on that debate. However, pride in one’s ethnic background does not automatically imply enthusiasm for lethal vainglory, let alone for mass murder.)

The Nazis use of Wagner as both symbol and inspiration, to adulate “manly” German pride and destiny, has blotted his reputation ever since their downfall. During World War II, German military heroes often got the signal reward of being sent to performances of his operas in their spiritual sanctuary, the theater Wagner himself designed in Bayreuth (in Bavaria). More gruesome, his music was allegedly played in guard barracks in concentration camps, to make the guards feel heroic (drugged, more like) so they could murder “sub-human” prisoners without hesitation or remorse. Joyously, in fact.

Thus, Wagner, though by any standards a great artist, may never again be known exclusively for his art, as Bach, Mozart and Beethoven are. He may always have the stain of heinous associations, made long after his death, about which it is impossible to be sure how he would have felt. The Nazis used his music to beguile the German people with things they (or at least, a great many of them) longed to believe about themselves, as demigods – unbound by the rules of lesser men – beliefs that would energize them to commit many of the worst crimes of the 20th century.

So I include this picture of his monument as a meditation on German cultural inclination to Fascism, for the way his music was used to stimulate, then sustain the Nazis’ exaltation of power as this world’s principle value. It is a caution that even creativity meant to offer us the experience of the sublime, like Wagner’s music, can be misapplied so as to lure us into the diabolical, and distract us from our sacred, humanity-defining duties as beings capable of empathy.

Art is not meant to so intoxicate a man that he is willing to be indifferent to hate in his heart or blood on his hands; but that was how Hitler used Wagner’s resplendent music.