CONTEXT: This piece from my visit to Cologne, Germany in 2016 doesn’t deal directly with Christmas. But I post it in honor of that holiday, 2022, to respectfully take issue with the premise – which increasingly pervades our outlook – that worthwhile human progress must come, more or less only, through the exercise of human reason. As noted in my ‘Jewish Bride’ essay recently re-posted, however much I praise and benefit from all the understanding, knowledge, technology etc. of our era, I deeply question if all other attributes of our nature should be disregarded or dismissed in its favor.

To cite an axiom of mine: Reason is not the only thing that makes us Human. To starkly illustrate that, I noted the Nazis’ diligent use of science in that recent post, as an instance of what may be called ‘brute Reason’ (as opposed to brute strength). Another example was Hitler’s T4 program, the covert murder of thousands of Germany’s physically and mentally handicapped people as ‘useless eaters’ who could only drain society’s resources and never contribute to them. Admittedly that was so, but despite euthanasia arguably meeting the standard of ‘logic’ as a basis for T4, it led to an unthinkably abhorrent course of action, repugnantly devoid of empathy – a humane quality whose value I propounded in ‘Jewish Bride.’

The following piece about Cologne cathedral speaks to the task to which Christmas calls us, and the wholly legitimate (in my view) human need for validation which may be found by complying with its summons. A need that should not be delegitimized – particularly by fortunate folk who have, or see, no need for consoling, sustaining hope – nor can be fully appeased with science’s gifts to us of greater comfort, more distraction and longer, better physical life.

Those are all marvels, but this essay suggests that many of us cannot find adequate meaning to life through them. It seeks to remind us of alternatives – generally, not feeling bound to seek exclusively rational answers – that will always be there for us if we need strength and comfort that otherwise elude us. And the humility to admit to such needs – to aspire to something unreachable by intellect alone, nor by other personal gifts – can be a first step in letting extra-rational hope ‘console and sustain’ us.

One need not be religious to be empathic, of course. But religious faith can offer a vantage point from which many of us may be inspired (given a last, vital boost) to act thus, piercing limitations that might otherwise keep us from doing so.

Cathedral Entrance: This is the end of the church with the great towers, unfinished until the 19th Century, when this grand portico was also added between them. The Industrial Age sculptors who executed this did their Medieval forbears proud; their carvings looked like they were cut by men who believed their work here might help admit them to Heaven, as their Gothic era predecessors may have exerted themselves to do.

The imagery above this door (in the space called the tympanum) may have some Biblical iconographic message, as art often did when literacy was scarce, but I didn’t even try to interpret it. Instead, I had long been intrigued by photographs of the Tympanum showing it with an unmistakable golden cast, so I looked closely to see if it was stone, rather than bronze, or some form of gilding. It is indeed stone, but clearly of a type different from that surrounding it, presumably chosen for its distinct color.

In a concession to efficiency, modern technology is used at the Dom to admit its 20,000 daily visitors. Its doors are sensor-driven transparent panels that glide back and forth horizontally (rather than swinging on hinges) with a soft whoosh.

The cathedral’s eventual completion during the Gothic Revival of the 19th Century was a rationalized, near-perfect expression of an extra-rational impulse. The skyscrapers of our era may scrape the sky, but they do not reach for Heaven. They are not meant to; their main goal is maximized economic utility.

Churches like the Kolner Dom, however, were meant to stretch for the celestial, connecting to its presumed benevolence in sharp contrast to a tumultuous world whose difficulties might otherwise be despaired of. They resonated of a hope worth enduring seemingly intractable hardships to attain, and sheltered embers of the West’s vitality until, in later times, ‘hope’ began to mean other (and more often, material) things than when this building was begun.

The great leveler mortality, and the right of every Christian to strive for Paradise, were formidable equalizers in the world of the Middle Ages. Inside a church, a prince, lord or knight might rate a better spot for mass, but otherwise, each person was truly “Everyman.” That is, animate dust, never truly, fully in control of his or her ultimate fate in this life. In this setting, a peasant, rough mason, thatcher or fuller might feel brethren to a king in ways they never would or could, elsewhere.

But they would not have considered sharing this most basic of all concerns as “Democratic” – a term and concept as alien to them as the planet Saturn. It was just an understanding among the faithful that all men were largely powerless, most individual concerns of scant import to the great expanse of time. And since Christ evidently held every person worthy of the offer of salvation to resolve the trials and vagaries of this life, it implied that, in the sight of God, no soul was less precious than any other (a seditious idea that would eventually help undermine the custom that high-born men were most entitled to rule, and reap, this world).

Even a Divine right monarch was Death’s subject, his crown and sway no more consequential than the degree of his lowest serf. It must have been a sharp reminder of actual priorities, in a world in which the rich and mighty were accorded such preeminent status, to realize that luminaries could die just as soon and suddenly as the poor and feeble; or be damned. To Medieval Christians, the presence of a deity presumed to be so saturated with love as to have gratuitously conjured the universe out of nothing, and bestowed the further gift on its only actively conscious beings – us, humanity – the option of of a path to escape the shadow of death was one context in which, assuredly, “All men were created equal.”

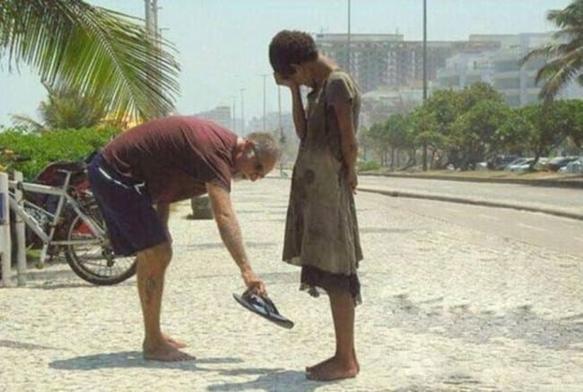

Conversely, speaking of inequality, it was just outside this portal that I saw the disturbing sight (mentioned in my original Facebook overview of my trip), of two men who seemed to be beggars, arguing, then forcibly grappling with each other. My German isn’t good enough to understand what they were quarreling about; possibly for the most advantageous spot to accost tourists. Their struggle was over quickly and with no visible harm done, but was a reminder that Cologne – wondrous as it may be to visitors – is not unlike most urban areas: Dense concentrations of people where some inhabitants occasionally feel forced to fight just to stay alive.

I’ve never seen homeless people in combat like that in my hometown, Chicago, but it probably happens anywhere people are reduced to desperation; an especially depressing, though instructive, spectacle when it happens amid First World prosperity like central Cologne or Chicago. And especially at the entrance to a building dedicated to proclaiming some of our loftiest aspirations.

(It would be interesting to know the back story of that fracas. Germany has a robust social safety net, and I learned that the Archdiocese of Cologne – which surely controls the Dom on whose threshold this struggle took place – also offers extensive charitable services for anyone in desperate need. I must wonder why those two men did not, or could not, seek out the different types of aid that are apparently available.)

Upsetting as that image was, I’m glad to have seen such a display of raw life, a jolting reminder, especially in view of my own relative financial stability, of how broken our world is for so many people.

The Kolner Dom is an awe-inspiring edifice, but ideals such as it betokens cannot be fully represented by the temples raised to enshrine them. Those would lift us higher than other creatures, and so can only really assert themselves by inspiring the quest for a world in which people neither need nor desire to fight, from those two men apparently frantic to stay alive, all the way to World Wars.

That seems to me a crucial duty of any great creed: Not only for most religious faiths, but especially for them, as they appeal to forces and inclinations at the upper limits of our nature. Such faiths exist to offer reason for hope, when Reason – used in isolation from the full panoply of the human spirit – may seem to justify, even to demand, jettisoning anything our minds cannot concretely encompass, as a sort of bloodless sacrifice to be performed in exchange for enjoying the practical benefits of the modern era. As if the wholly human dread of reverting to the darkness were some flaw a modern person should simply be able to suppress with machine-like equanimity.

The semi-feral tussle I witnessed – amid a rich, rebuilt city, laid waste to frustrate the infernal Nazi agenda that people should emulate the kill-or-be-killed behavior of wild animals – at the doors of a place meant to invite us to better things, accentuates that we collectively still have many thresholds to fully cross.