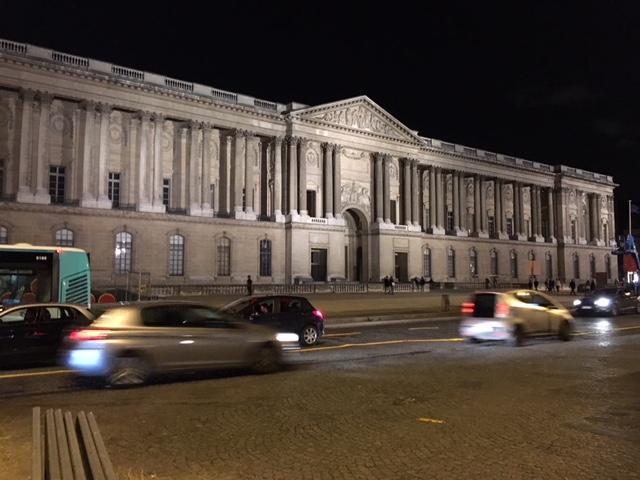

CONTEXT: From my 2016 Europe trip, previously posted online: This image of a high-Baroque church, built in gratitude for Vienna’s deliverance from what was to be its final Plague, in 1713, has great historical implications. But in this post, I graze on issues and forces that interweave with history, but do not necessarily fit within its (presumed) logic. Or any other.

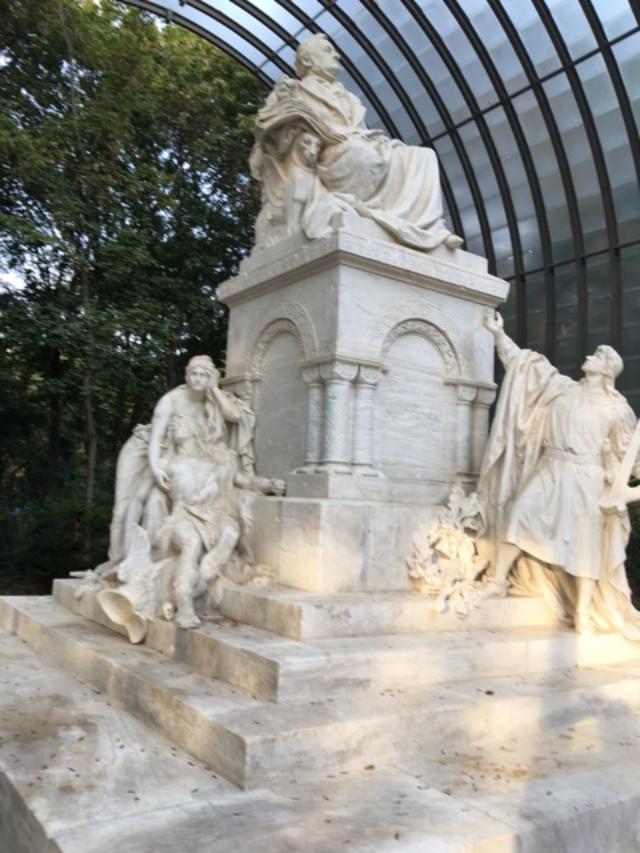

An outburst of piety expressed in paint, marble, gilding, etc. The whole interior is a carefully orchestrated riot of decorative elements, but the depiction of Saint Charles Borromeo (name saint of Austria’s ruler at the time, Holy Roman Emperor Charles VI) over the altar, in the middle of this picture, is the focal point. He is being “assumed,” bodily into Heaven – which, referencing the Old Testament, is suggested in a triangle above with the most sacred name of the God of Israel in Hebrew letters.

Historians (as I style myself) must sometimes caution against Presentism: That is, when living people judge events and artifacts from the past shorn of their context of culture and then-current events, by their own (contemporary) frame of reference. This can be quite misleading; the Karlskirche, built in roughly the same era as Saint Paul’s in London, may seem to some today a misallocation of energies (it was also an expression of imperial Hapsburg prestige). But consider: What might future generations think of Our priorities? Especially if they are trying to survive on an Earth deeply degraded by our unconsidered material self-indulgence?

When this was being built, it was not clear that humanity could or would ever be able to control the world in such a way as to vanquish terrors like Plague – that is, deflating physical phenomena to predictable, manageable processes.

People then would no doubt be glad for an end to pestilence, along with reliable sources of food, clean water, heat, light, etc., such as we in the 21st Century enjoy. But they might have a question for us: What point does human life really have, if every facet of it can be reduced to mere mechanisms, seemingly devoid of any potentially collective (not just individual) ‘consummating’ purpose? This church – like most places of aspiration – offers a vision of a world fundamentally better than the one we can perceive, not just tidied up somewhat.