Every year, I post a version of ‘Oh Come, Oh Come, Emmanuel,’ perhaps the most venerable song of Christmas. With Medieval roots, allusions to the Old Testament, its lyrics originally in Latin as ‘Veni, Veni Emmanuel,’ it is often performed with grand solemnity. Or when sung in English, in a tone of quasi-theatrical religious effusion.

But I feel its innermost nature, rather than solemn or theatrical, is awed reverence, hushed as the light of twinkling stars and evoking a limitless force that sustains them. So this year I have chosen an unadorned piano solo, displaying a common English translation. Those words will be my focus here, for when not inscrutably cloaked in Latin, they are as meaningful and compelling as the austere, ageless melody.

Especially consider ‘ransom captive Israel.’ It could be a reference to the Babylonian Captivity, or Roman oppression of the Jewish people. But there may be a broader interpretation: ‘captive Israel,’ refers not just to the Chosen people but to all children of God, everywhere and always, in lonely exile outside the Gates of Paradise since the fall of Adam.

Without speaking stridently, this song echoes ancient inspiration that can brighten our entire condition, conveying melancholy at human woe, yet encouraging us in hope for ‘power o’er the grave.’ And it poignantly addresses our desire, unspoken or unrecognized, for relief from the disappointing, browbeating world most of us experience, relief that may materialize ‘in cloud and majesty and awe.’

Jesus, these words cumulatively intimate, offers rescue from the sense of exile from the Edenic world that was, and is, supposed to be. And they subtly, but insistently affirm faith that, in the hands of Providence, all will be well. If only in an ultimate dimension, which we can never fully perceive.

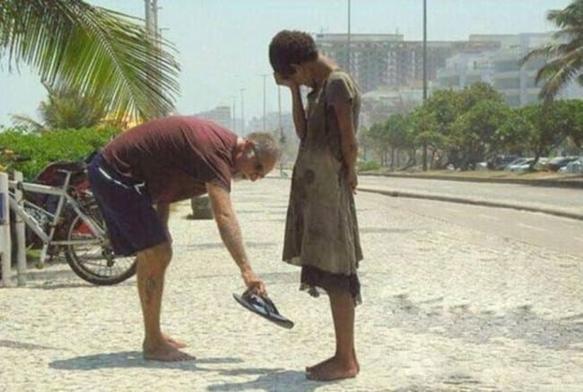

Most people, at some time in their lives, will feel the sting of events beyond their control, no matter how autonomous or gifted they are. Our culture nudges us to focus (ever so profitably) on our individual selves, but ‘We’ are more marvelous together, than any of us alone can ever be.

So to perceive our value only in terms of the Self is to reject a sense in which we might, effectively, attain eternal life. That is, by living so as to contribute to the welfare of humanity after us, so that they will benefit from any benevolence we contributed or sustained. As opposed to living for ourselves alone, and thus simply vanishing when our bodies die.

‘Death’s dark shadows put to flight.’ The premise, on reflection, is not necessarily that our physical lives can be eternal; it is that our presence in this life need never disappear entirely. Jesus incarnated faith that we are worth far more than just our imperfect Selves, and pledges that faith to us, forever. This carol’s tone bespeaks grievous discouragement, but also hope that its longed-for remedy appears at Christmas.

The coming of Christ, who overcame the Self to redeem all Others, may offer solace to anyone who hopes there must be more to us, and our existence, than the intellect alone may ever compass.

As events, fate or passage of time diminish our individual deeds, unique qualities, advantages or burdens, all that remains to each of us, for better or worse, is the substance of our own humanity. And it is for refuge in that substance to which these words allude, by overwhelming grace that may ‘close the path to misery.’

One cannot, in any sense, truly grasp infinity, but one may yield to and merge with it, as this music pleads by proxy. Christ’s coming, mission and vertiginous love assert our fundamental value, merely by the exercise of the trait that distinguishes us from other life forms; the ability to reason – empathically.

It is less important that the existence of love like that can be factually proven, than that we act as though we are moved by its example. For that is the promise Jesus represents for all who grasp it, and reciprocate it, with lives that perpetuate the cycle of giving, joyously, that propelled Creation itself.

This timeless melody inspires awe, but its words of both jubilation and serenity also reward contemplation. Always, but especially in this season of Emmanuel, ‘God with us.’