Today, November 2, was the birthday of my late mother, so I dedicate this post to her memory. Also to honor and advocate for the power of kindness and wise compassion, such as she often showed. That is relevant to my overall topic here, about our potential to advance beyond archaic lower impulses.

November 2 is also ‘All Souls Day’ in the Catholic tradition, when we may reflect on all those – not just our loved ones or co-religionists – who have gone before us in the great, turbulent narrative of Mankind.

Both those references, to advancement and reflection, apply to this post, which comes from my recent October, ’24, visit to Europe (London, Paris, Bordeaux). It deals specifically with a dark chapter of that narrative, one that our civilization has largely left behind, and with the hopeful implications of our having done so.

The word ‘Tyburn’ still resonates among many historically aware people. It is the name of a site originally beyond the western fringe of London (which has now grown up around it) where, for more than 500 years, men and women (and sometimes, children) convicted of capital crimes in the city were executed.

It lingers in the cultural semi-consciousness as a place of injustice, cruelty, indifference (as well as deep grief and sorrow) and other base attributes supposedly indelibly in Human Nature. Yet Tyburn may also now be considered a point from which ‘Human Nature’ has arguably taken a substantial step forward.

Perhaps the most somber incident during my 2016 visit to Europe was in Amsterdam, when I stood outside Anne Frank’s House, where she and her Jewish family hid from the occupying Nazis, only to be betrayed, resulting in most of them dying in the Death Camps. I had gone there immediately after viewing works by Rembrandt in Amsterdam’s Rijksmuseum, a short distance away.

In my eventual online post about that episode, I referred to the end points of my walk to the House – starting at a venue of breathtaking creativity, but ending at one of abominable cruelty – as ‘A summit and an abyss of human endeavor, separated by a brief walk, yet from different worlds.’

Tyburn is no direct analogue to the Anne Frank House. If anything, its eventual fate reflects the sort of peaceful evolution which the Nazis, rabid advocates of the law of the Jungle, disdained and tried to thwart. But like the Frank House, it too, is only a short stroll from a locality of preoccupied vitality.

London’s largest retail district, Oxford Street, bustles immediately east of Tyburn, oblivious in its materialist spirit to the nearby place of morbid memory. Oxford’s commerce is hardly as exalted as the artistry on display in that Amsterdam museum, but like it, is an acute contrast to the mournful spot that Tyburn was for many generations.

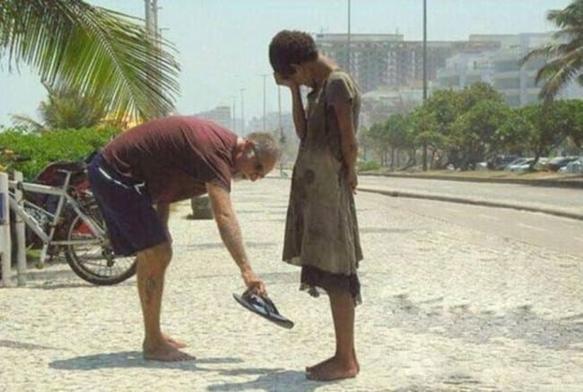

The accompanying photo shows the extremely modest memorial – possibly thus due to shame by British society today at what was done here – to ‘Tyburn Tree.’ That was a gibbet which stood here from 1571 till the mid-Eighteenth Century, consisting of three vertical poles with horizontal beams between them, upon which multiple condemned persons could be hanged simultaneously. Before and after the ‘Tree,’ Tyburn was used to publicly carry out executions, till those were moved to Newgate Gaol (Jail) in the 1780s.

I had explicitly planned to go see this plaque when in London. An ancient city, it has many fascinating attractions, but I wanted to seek parts of its story beyond ‘attractions.’ Tyburn is one such, which should be remembered and pondered, as it so long epitomized how fearsome and punitive our world once was. So I arranged for my sister (who accompanied me in London and Paris) to browse an Oxford Street store nearby, while I made my semi-pilgrimage to this focus of melancholy.

If one feels any need to reflect on dark, sad aspects of history, Tyburn is certainly a ‘focus’ to do so. Over the centuries of its use as a place of judicial killing, masses of ordinary folk were put to death here at the behest of a callous, hierarchical society, making it one of the grimmest places in the world before mechanized killing. (The Tower of London, more famous as a place of executions, was used to do away with the high-born who had offended the Crown. Commoners were consigned to the disgrace of Tyburn, with its jeering spectators and general chaos)

One of the most shocking things about Tyburn to 21st Century sensibilities is how many people were hanged there for petty larceny, a relatively trivial offense no right-minded person today would dream warranted dying for.

Statistics of how many executions there were, how many were hangings, how many of each sort of crime, etc. may be available in scholarly sources, but I did not seek those out for this post. For context however, it is believed that, during its 500 years as the main site where the law put Londoners to death, several thousand were slain here.

My interest is more in what such a phenomenon can tell us about who we were, and by implication, who we have become, and still are becoming. Bluntly, Tyburn was a place where English society proved that it valued property more than life; or at least the lives of the ‘lower orders.’ My unverified impression is that most of the people dispatched here were hanged for often paltry crimes such as the theft of the equivalent of 3 days’ wages. Again, these were offenses for which no modern person should ever accept that capital punishment was appropriate.

Thus, however many ‘souls’ were hanged here for such deeds, it was too many.

Those found guilty of more serious crimes, like murder and treason were also disposed of here, but again, class status played a crucial role – especially in cases of rebellion/treason. Noble folk found guilty of such were usually beheaded in, or near, the Tower, while commoners endured the gruesome ignominy of Tyburn.

Far worse, traitors from of a lower social ‘station’ were ineligible for the relatively merciful death of beheading, reserved to those ‘gently born.’ Lower status men were subjected to the full, horrific, meant-to-terrify traitor’s death, including being torn apart (quartered) by horses, along with other torments.

Thus, what happened at this site for so long should offend us today from various perspectives: First, it reflected a generally savage environment. Also, no doubt, many of the condemned were innocent of the crimes with which they were charged, but got swept up by a court system whose real concern was the protection of the elite’s privilege, property and prestige, more than individual guilt or innocence.

Worse, many, if not most of the victims did things that absolutely wouldn’t rate a death sentence today (even if such still existed). Capital punishment was applied to such a broad range of crimes that it was seemingly the preferred response to almost any sort of getting out of line against the social order, or even against mere convention.

Especially such as hanging for theft, when the guilty party may have acted out of desperation, starving in a culture whose priority was not the general welfare, but ferociously upholding a self-serving Status Quo. Like gibbeting a man for stealing a week’s bread to feed his hungry family when he could find no honest means of doing so. He got snared in a web in which his ‘betters’ got, and kept, the best of everything.

Worst of all in my view, even those who committed deeds we still abhor, like murder and rape, were often made to suffer in ways so perversely cruel that arguably they negated any moral high ground of the authority that would impose them. They were naked, cathartic revenge and intimidation, masquerading as justice.

How can any law that mandates human beings be disemboweled (part of the martial penalty for treason) consider itself to be defending civilization, rather than legitimizing barbarism? Any society that imposes such atrocities is acting out of organic self-interest, arguably little, if at all, better than those upon whom it inflicts them.

All of us today can, and should, be relieved that we are now living in a world where such things cannot, or should not, happen to us (or to anyone else). Slipshod convictions are far rarer, and ‘cruel and unusual punishment’ is expressly prohibited. Even non-lethal penalties during this timeframe were often ghastly, including whipping, branding and pillories.

Returning to the photo, this plaque is not at all prominent, set in a traffic island (ironically, triangular like the setup of the ‘Tree’ itself). Most of the drivers passing it probably don’t even know it is there, or don’t register that it marks a miasma of injustice (‘legality’ notwithstanding), the scene of uncounted deaths over centuries of enforcement of societal norms set by those who benefited most from them. To say nothing of the ongoing bestialization of a citizenry already roughened by the struggles of daily life.

As cars roared around me, I said a prayer for all the Souls whose mortal lives were ended there: Those wrongly accused, those guilty of crimes we would now consider misdemeanors, and those made to suffer in ways we couldn’t even find people today willing to inflict, regardless of the offense. Even for the genuinely guilty, and truly evil ones, of whom there must have been many, themselves often victims of squalid realities.

The former site of Tyburn is now mostly overlooked, but I had felt some compulsion to visit it. I cannot believe that most of those ‘souls’ deserved what was done to them here; not in severity, and possibly, not at all. I mused – hoped? – that my lamentations might at least partly offset the sheer dreadfulness this place both witnessed and reflected, and might minutely help compensate for the inequity of their wrongful sufferings and death being forgotten. Or just ignored.

As the Colosseum, where bloodshed was staged as entertainment, is now a ruin, so Tyburn – where a public reduced to semi-savagery by the brutishness of their grinding existences came to enjoy watching brother beings perish – is now long gone. An abandoned, shameful echo of life as pitiless conflict, and a mass failure of empathy for ‘brother beings.’

There are likely still some people today, in 2024, who might regard the agony of others as a diversion, as the mob often did at Tyburn. But such persons are now repugnant outliers; our culture has, as a whole, grown beyond such bloodlust. Most people today (I fervently want to assume) would be aghast at the idea of public hangings, or worse, as amusement.

All of which may explain why this site is now so modestly marked. Some acknowledgment of the enormity it represents may have seemed needed for propriety – but not to be proudly emphasized. Like a gross transgression committed in one’s raw immaturity of which one grows to be remorseful, ashamed, and even penitent. (As far as I know, British law today does not allow Capital punishment for anything, even Regicide; killing the King.)

I choose to interpret the transition of English culture beyond the need for a place like Tyburn and the values it was used to oppressively sustain, as mirroring the gradual improvement of our species. As proof that our ability to reason may manifest as an inclination to empathize. And as demonstrating that any assertion that Human Nature is immutably corrupt and selfish is not indisputably true.

Those who believe that facts, such as evidence of recurrent human baseness, must be accepted at face value, are free to do so. Those like me, who have faith that events may have subtler implications beyond their face value alone, are equally free (and in my opinion equally justified) to follow that path instead.

Such a hope also is a tribute to my mother; indeed, to most mothers. Perhaps the kindness, sympathy and tolerance that their role in bearing, protecting, and nurturing vulnerable life requires of them will, slowly but inexorably, continue to shape our world more than primitive impulses we should strive to subdue in order to deserve, and to attain, our fullest humanity.

Impulses like valuing our property (and our prosperity) more than others’ lives. That we should leave more and more ‘Tyburns’ behind, and recall them with only shame and a shudder, as we come to regard each other less mainly as competitors for survival. Such is an outmoded habit, an artifact starkly unsuitable for our brighter Age.

Just as the Tyburn Tree would be.