The title of this post is the traditional English translation of the name of a classic German Christmas carol, ‘Es ist ein Rose entsprungen.’ It refers to a rose, lovely and fragile, that nevertheless blooms amid the cold and darkness of Winter.

The rose referred to in those lyrics is Jesus, who offers light to the world, and not just amid the darkness of winter. His coming at Christmas, and the attached photo are connected by imagery of the rose. In this case, specifically, by a White Rose.

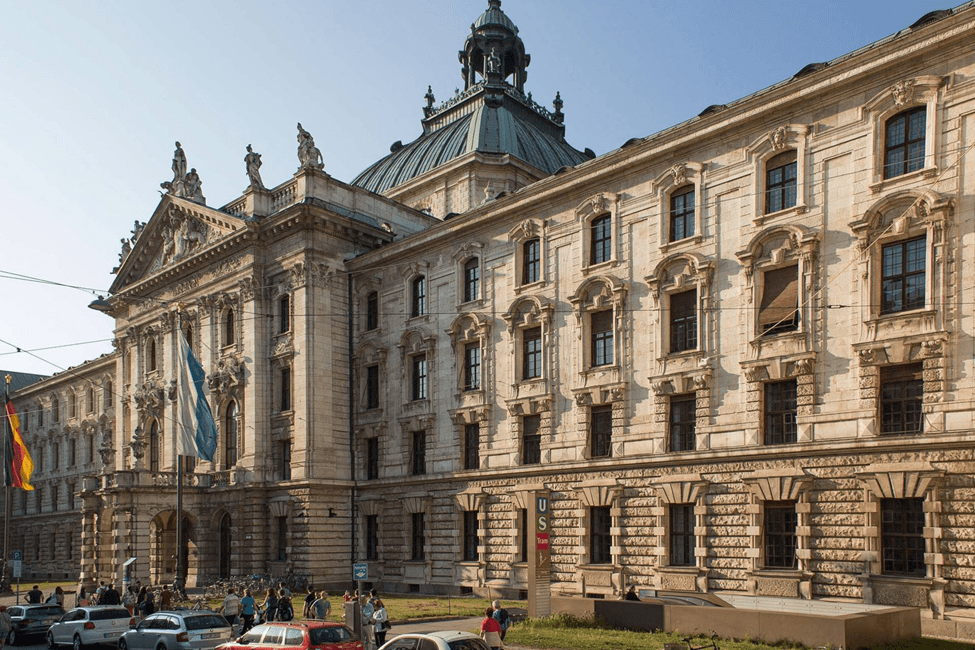

I took this during my visit to Europe last October. It shows Bavaria’s main courthouse, the Justiz Palast in Munich. In February of 1943, as the course of World War 2 was shifting irreversibly against Germany’s Nazi rulers, this building was the site of the trial of brother and sister Hans and Sophie Scholl, and Christoph Probst (arguably the intellectual epicenter of the circle), principal members of ‘Die Weisse Rose,’ the White Rose, code-name for a group of young resisters to Hitler’s regime. Its members had profound moral hostility to Nazism, and some, including Hans, had served in the Army on the Russian front, and witnessed German atrocities in the USSR.

The Scholls and their co-conspirators were patriots clear-sighted enough to know by then that the war was lost, despite the government’s frantic lies about its course. They wanted to save their beloved country from complete destruction by the overwhelming power of the enemies Hitler had brought down upon it. In fact, this courthouse still bears scars from the bombing that would befall Munich the next year, 1944.

But beyond patriotism, Sophie and Hans were also impelled by deep, resolute Christian faith. They knew perfectly well the awful risks they faced at the hands of the Regime’s savage Gestapo secret police, but felt stiffened to resist it by writing, printing, and spreading vehement anti-Hitler leaflets (considered high treason). They believed their creed, if sincere, obliged them to resist evil, no matter the danger.

Presumably, knowing that Jesus had accepted giving up His life for the world figured into their commitment. The White Rose’s members did not seek martyrdom, but did not shrink from its peril either.

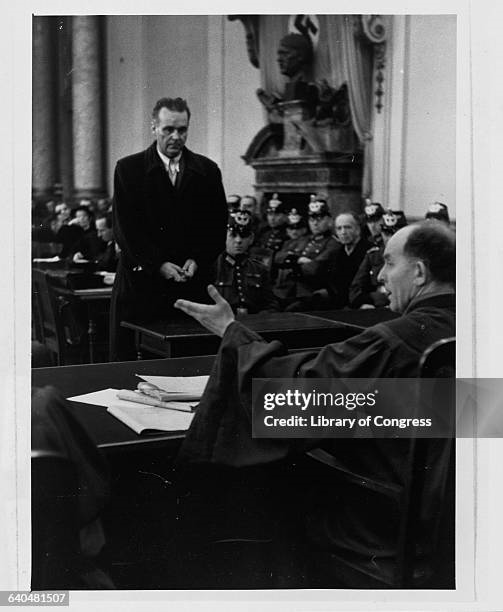

Sophie, probably because heroism is not usually associated with women, has become a legend of principled resistance to evil. But she did not act alone; after being caught (by tragic happenstance) distributing their leaflets, she, Hans, and their associate Probst were arrested, tried, convicted, and beheaded. Sophie’s captors were so astonished by her courage and resolve, they offered to mitigate her guilt from the capital crime with which she had been charged, for they had surely never encountered such authentic nobility by doctrine-spewing Hitler Youth. But she refused to accept, forthrightly stating that she would not recant what she knew to be true and rightful, and bend to the ruthless might and criminality of Nazism.

I had not sought this building; only walking past it, and reading ‘Justiz Palast’ did it occur to me it was likely where White Rose members were tried by the screaming judge Roland Freisler, ‘The Fuehrer’s Executioner.’ To suddenly grasp what had happened here, then reflect on the soaring courage and honor once shown within was both arresting – I stopped mid-step as that realization came over me – and awe-inspiring. Unlike the recovered colored light in Notre Dame in Paris (described in an earlier post), here, my wonder was engendered not by powerful, inadvertent visual symbolism, but directly by human deeds.

If seemingly, more-than-human deeds.

The passionate idealism of the White Rose was the strongest possible rebuke to the carefully curated cruelty and fanaticism of the Hitler Youth, saturated by the Nazi state in racist, bestial ideology. If callow, juvenile men can be manipulated into believing that their worst instincts are actually nobly warlike, the Scholls and others showed how youthful ‘passionate idealism’ may also see right through malevolence, and valiantly oppose it.

If the White Rose members had been exclusively logical, they would have kept their mouths shut, their heads down and their non-combatant status as university students intact. But they did not, for they discerned a duty more precious than their very survival. In serving that, they did far more than deserve to be remembered. They have left a source of inspiration like few who have ever lived, igniting the full power of the soul to act beyond transient concerns, in the interest of values whose urgency never fades. Their determination starkly, absolutely contrasted with some of history’s worst acts of inhumanity.

The example of their bravery and self-sacrifice matters critically in a world where brute force such as (but not restricted to) Nazism too often seizes control of events. Again, the Scholls and Probst had stalwart Christian worldviews, so it seems likely that Jesus’ care for the whole human family – the antithesis of Nazi racial theory – must have been part of their inspiration.

(Of course, such devotion can arise from non-religious sources, but in this case, their intensely personal, if not rigidly formal, faith enabled these young folk to confront death, rather than yield to its menace.)

It is often in seemingly irrational deeds like theirs, floridly contrary to Self-interest, that the scope and potential of our humanity may sparkle most brilliantly. In such cases, we may benefit from decisions that cannot be rationalized, as much, or more, than from many that make perfect sense.

The White Rose was a bloom that will never wither, just as Jesus is the rose, blooming at Christmas, abiding despite all the malevolence in our oft-sinister world. By not doing the sensible thing, the Scholls showed that decency and honor have not perished – in a way adjacent to how Christ showed the same, in love and kindness. I am not nearly brave or strong enough to have done what they did, but am inexpressibly grateful to them for showing that, however implausible, it is not impossible.

Indeed, I have noted in other writings that our finest actions are often not our most rational ones. Surely, all readers of this post know of instances when people braved danger or suffered pain that they didn’t have to, out of simple, heroic decency. Or purest love.

Though this post seeks to honor the White Rose as an instance of aspiration adequate in scope for Christmas, nothing I write could possibly do justice to the splendor shown by its members, and especially its martyrs. The best I can do is to marvel at the implications of their deeds and ethics.

As long as we have hearts to swell and eyes to tear with admiration, members of this tiny circle may be remembered; and emulated. They did not stop Hitler or his monstrous war, but they proved that not even his towering evil could exterminate righteousness, for it was, and is, still to be found around us. An invaluable lesson and a spectacular bequest to the world.

I cannot accept that the human sphere must be merely a cynical contest of genetic material, of our individual gifts or our burdens. The White Rose was proof that such random circumstances can be exceeded, as Christmas suggests Divine hope – and faith – that we can each, conceivably, resolve to rise above such constraints. And far from being exclusively the refuge of the weak and passive – as the Nazis derisively presumed – the Christianity of this trio, at least, made them guerillas for Christ.

The legacy of the Scholls and Probst reminds us how even the most demonic sway in our terrestrial element can never fully overcome the life force that summoned it, in the beginning, as ex-nihilo Creation. When hope guards rectitude as indispensable as that the White Rose defended, all the shadow in existence cannot, and did not, subdue it.